I read an article by a man named Ronald Chase, a neurobiologist (and apparently gastropod sex expert?) who made the decision to pursue his field instead of going to law school after his brother was diagnosed with schizophrenia:

"I began to believe that mental illnesses—at least the major disorders like schizophrenia—are not in the mind but, rather, in the brain. I reasoned that no nonphysical thing, a mind, could possibly govern a physical thing like the brain, and it was the brain that mattered, because it controls behavior. The mind, I concluded, must be an aspect of the brain’s function."

This got me thinking about the differences between mental and physical health. I thought about the 24-year-old woman who was recently found to have been living without a cerebellum, and my friend's token "crazy ex" in college whose irrational behavior towards the end of their relationship was found to be literally caused by a benign tumor in her brain that was putting pressure on the part of the brain that controls reasoning. As much as we like to think of our personalities and intelligence and higher processes in general to be something ethereal or mystical, the truth is that we are all organic machines, and our brains aren't that different from computers — or, for that matter, any other organ in our bodies. The difference between depression and Irritable Bowel Syndrome is really just about which part of your body the problem exists in (one makes you feel like shit, and one makes you literally shit?).

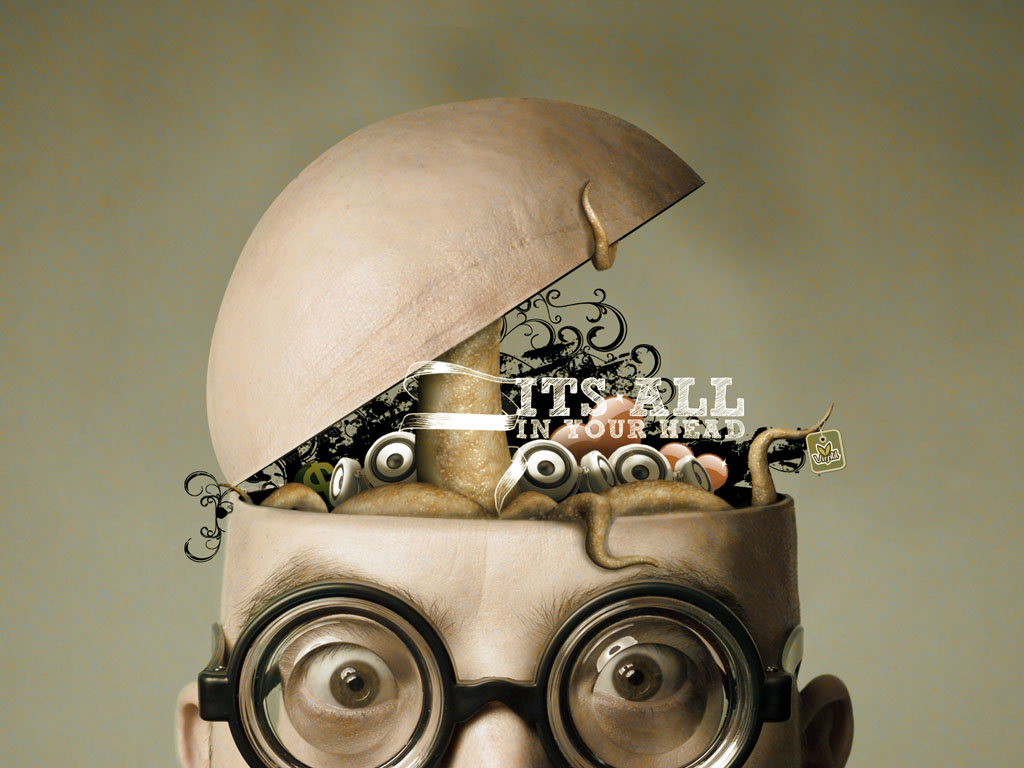

And yet, our culture doesn't look at mental health as something that can be maintained or looked after — even when the symptoms are embodied. It's difficult to explain, but when I'm struggling with my ADHD, for example, I can feel it in my body: the pain inside my head, my heightened blood pressure as the anxiety builds when I'm having trouble focusing. Sometimes the effort it takes for me to concentrate on certain things is physically exhausting. But no one takes it seriously because it's not "visible," because it's not an ailment you can see.

But you can't see Crohn's disease, either. You can't see the flu, or AIDS, or pneumonia, or food poisoning. They're not visible either; they happen inside your body, just like anything relating to mental health. The only difference is that they occur in organs that aren't the brain, I guess because we don't ascribe as much metaphysical value to our stomachs.

But why not? Seriously, why not? Why aren't "Mental Health Days" legitimately respected? If you tell your boss you've got a stomach ache, you're free to stay home and heal, no questions asked. But if you tell your boss that you're feeling depressed and stressed and anxious and generally overwhelmed with the world and you really need to stay home and watch trashy television in your PJs all day, it probably won't go over as well, for no other reason than that the sickness — be it temporary, or a permanent condition — is physically in your head, instead of another part of your body.

This extends to language as well; we've (hopefully) all learned by now that it's not okay to use words like "gay" and "retarded" in derogatory or pejorative contexts. What about "dumb," which derives from muteness? Or "crazy," or "psycho," or "bi-polar," or hell, "ADD" (half the reason I was ever diagnosed with ADHD is because I was using the phrase flippantly and my mother didn't realize and became concerned)? I'm not here to "police language," but it was interesting to consider that no one ever says, "That's so cancer," or "Oh yeah, she's totally got tuberculosis, bro." No, instead it seems that explicitly-physical illnesses are universal understood and acknowledged so as not to be used as cheap punchlines or ignorant shorthands.*

Let's take this a step further: I bet we all know someone who has a sick relative that they're often charged with taking care of. Whether it's the aforementioned Crohn's, for example, or a loved one dying of cancer, society looks on those caretakers with sympathy. Don't get me wrong, there's good reason for that — taking care of a sick family member can be a lot of work, lots of stress and sacrifice with little return on investment (not that "helping someone close to me stay alive" is a minor reward, but you know what I mean). On the other side of the equation, people who are forced into the role of caretaker for a relative with mental health problems? We look on them with pity. Caring for the exclusively-physical health of a loved one is seen as a noble sacrifice, but caring for the mental health of a loved one is seen as a burden. But again: what's the real difference?

No, really: what's the difference? And I'm really not trying to poo-poo everyone's fun as some kind of language police; I'm genuinely trying to understand why it is that our culture evolved to treat some invisible diseases and conditions as being different or less-real than others. Hell, even neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer's and ALS are treated with sympathy and respect; but then, there's a physical aspect to them that people can identify. But if a condition affects your neurological functions, that means it's in your brain, which means it's in your body, which means it's physical. Someone with Irritable Bowel Syndrome might spend a lot of time in the bathroom, while someone with clinical depression might spend a lot of time in bed because they have a literal physical difficulty to fully wake up; guess which one is considered an excuse? It's perfectly acceptable in our society to be flip with self-diagnoses: "I'm feeling so manic / depressed / bi-polar / ADHD / anxious / etc. today." And yet, no one says "I've got a little Crohn's today, if you know what I mean" when they're having diarrhea (I don't know why I'm picking on Crohn's so much; blame Mark Millar).

The question remains: how do we change that stigma? How do we make people understand that mental health is physical health, and that a few pills here and there might make it easier to cope but it doesn't make the invisible problem go away any more?

*For the record, I know that I personally still use "dumb" and "crazy,", which I can either excuse as general hypocrisy, or as an example of the constant evolution of language which — for better or for worse — does occasionally stem from some questionable roots (like how "vagina" is literally derived from "sheath for a man's sword").