I will come to a time in my backwards trip when November eleventh, accidentally my birthday, was a sacred day called Armistice Day. When I was a boy, and when Dwayne Hoover was a boy, all the people of all the nations which had fought in the First World War were silent during the eleventh minute of the eleventh hour of Armistice Day, which was the eleventh day of the eleventh month.

It was during that minute in nineteen hundred and eighteen, that millions upon millions of human beings stopped butchering one another. I have talked to old men who were on battlefields during that minute. They have told me in one way or another that the sudden silence was the Voice of God. So we still have among us some men who can remember when God spoke clearly to mankind.

Armistice Day has become Veterans' Day. Armistice Day was sacred. Veterans' Day is not.

So I will throw Veterans' Day over my shoulder. Armistice Day I will keep. I don't want to throw away any sacred things.

What else is sacred? Oh, Romeo and Juliet, for instance.

And all music is.

Kurt Vonnegut would have been 92 years old, Veterans Day 2014 — which is particularly ironic because although Vonnegut was a veteran himself, his anti-war sentiments were anything but subtle ("I'll be damned if it was worth it," he once wrote in a letter to home when he was deployed). Admittedly, he may have been biased, seeing as how he was held as a POW in World War II during the bombing of Dresden, which inspired his psuedo-autobiographical-time-travel-alien-abduction novel Slaughterhouse-Five. That's the power of science fiction, kids: when a personal experience is so traumatic that you struggle for years to find a way to write about it, just add some Tralfamadorians and some non-linear structure, and somehow through all that fantastical dressing, you will find the heart of the story that you were otherwise too close to and too scared to find.

Consider these bits, from 1961's Mother Night:

There are plenty of good reasons for fighting," I said, "but no good reason ever to hate without reservation, to imagine that God Almighty Himself hates with you, too. Where's evil? It's that large part of every man that wants to hate without limit, that wants to hate with God on its side. It’s that part of every man that finds all kinds of ugliness so attractive.

"You hate America, don't you?" she said.

"That would be as silly as loving it," I said. "It's impossible for me to get emotional about it, because real estate doesn't interest me. It's no doubt a great flaw in my personality, but I can't think in terms of boundaries. Those imaginary lines are as unreal to me as elves and pixies. I can't believe that they mark the end or the beginning of anything of real concern to the human soul. Virtues and vices, pleasures and pains cross boundaries at will."

Living, dead, or purely coincidental, I count Vonnegut amongst my favorite authors, and his wry sense of humor, fourth-wall-breaking, and brilliantly simplistic observations about human nature have served as a major inspiration for me in my work. My relationship began when my father bought me a copy of Timequake when I was 12, which I was way too young to fully appreciate. But even though I didn't have the words or education to explain how or why I was affected by his metafictional-memoir-cum-failed-novel, it still struck a serious chord, and helped further cement for me the power of fantastical fiction, and how all those weird elements can combine to make a story that much more human.

There's a lot about Vonnegut that can serve as inspiration for storytellers. I keep his "8 Rules for Fiction" in mind whenever I write a story. Here's the full text, which originally appeared in the introduction to his collection Bagombo Snuff Box:

- Use the time of a total stranger in such a way that he or she will not feel the time was wasted.

- Give the reader at least one character he or she can root for.

- Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.

- Every sentence must do one of two things—reveal character or advance the action.

- Start as close to the end as possible.

- Be a sadist. No matter how sweet and innocent your leading characters, make awful things happen to them—in order that the reader may see what they are made of.

- Write to please just one person. If you open a window and make love to the world, so to speak, your story will get pneumonia.

- Give your readers as much information as possible as soon as possible. To hell with suspense. Readers should have such complete understanding of what is going on, where and why, that they could finish the story themselves, should cockroaches eat the last few pages.

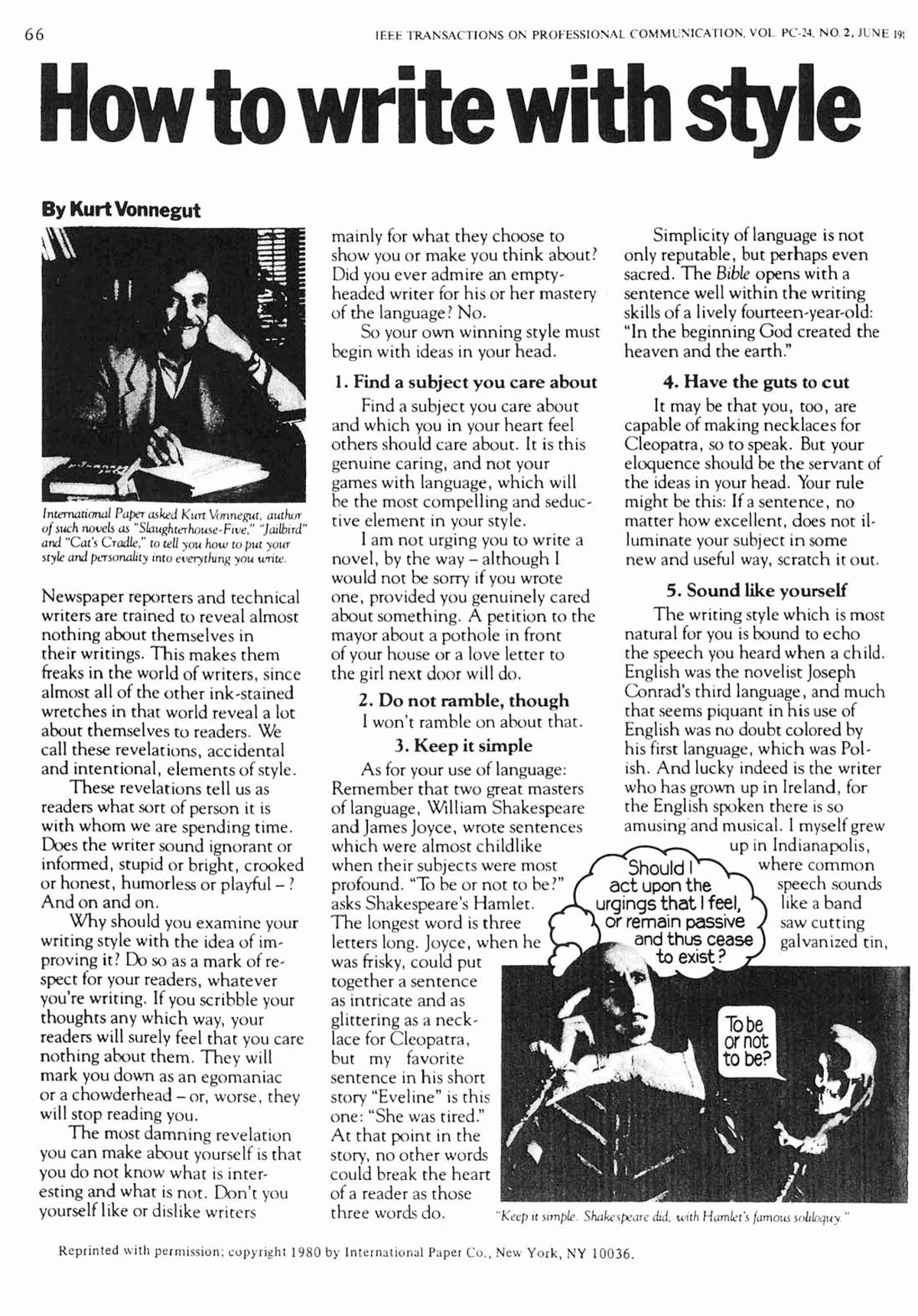

He also laid down some pretty solid rules for "How To Write With Style," which were originally published in the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers' journal Transactions on Professional Communications in 1980, though I haven't the faintest idea why.

But my personal favorite writing advice from Vonnegut is his lecture on "The Shape of Stories," which began as his rejected Master's thesis proposal from the University of Chicago (he would later be granted his anthropology degree for his novel Cat's Cradle, which is basically the foundation of my functioning religious beliefs). Here's a video of his theory, accompanied by a handy diagram courtesy of OpenCulture:

But Vonnegut's most important advice comes courtesy of his 1959 novel The Siren of Titan:

"A purpose of human life, no matter who is controlling it, is to love whoever is around to be loved."

So it goes, yeah? Now I'll you with this: an actual recording of Kurt Vonnegut himself reading from Slaughterhouse-Five. You're welcome. Happy Armistice Day.